Soldier, Settler, Storyteller – Part 1

In the vast, untamed expanse of the Dakota Territory, where rolling prairies met rugged hills and the sky seemed to stretch on forever, my cousin William Presley Zahn stood on a divide between two worlds, his life poised to thread through the heart of an emerging nation’s turmoil. This land, shadowed by the lingering conflicts that would scar its history, was thick with the tension of imminent battle, the soil beneath soaked in the blood of fallen men. Zahn, reassigned as a soldier to the burgeoning outposts scattered across the landscape, was soon to become a crucial liaison between the U.S. Army and the Lakota people.

Born on October 25, 1849, William was the eldest child of John and Esther Zahn, nee Stambaugh. His early years unfolded on a secluded farm near what is now Pymont, Indiana, where life was defined by the rhythm of seasons and the bonds of a tight-knit community, centered around the sparse social and educational gatherings at the local church.

The Civil War had just ended, leaving the nation to grapple with its scars. The South was mired in Reconstruction, while the West simmered with the tension of the Indian Wars. Railroads snaked across the country, stitching together a patchwork of states into a unified, yet still fragile, nation. It was 1869 when William, drawn by the call of duty and the promise of life beyond the fields of his youth, enlisted in the army. By 1870, he traveled up the Missouri River, the paddlewheel steamer churning through muddy waters, the scent of damp earth and the cries of waterfowl filling the air as he approached the northern reaches of Dakota Territory. As a member of Company G, 17th U.S. Infantry, William was ready to forge his path in a land on the brink of transformation.

Spring of 1872 marked a new chapter for Company G as they were tasked to escort the Northern Pacific Railroad engineers along the winding course of the Heart River, a tributary stretching 180 miles across the stark landscape of Western North Dakota. Later in the Spring, William found himself embarking on a 66-day journey with the Yellowstone Expedition, a mission critical to the railroad’s efforts to chart a course along the Yellowstone River. It was a time of frequent and fierce skirmishes with the local tribes, their encounters peppering the land as far as Pompey’s Pillar. This was a site notable for its association with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which stopped there in 1806.

After these arduous weeks, William returned to the Standing Rock Cantonment, known as Fort Yates. It was here, amid the strict orders and sharp cultural divides of military life, that his life took an unexpected turn. His heart aligned with that of a Lakota woman named Winyan-Waste, the daughter of Chief John Grass. In a setting where military discipline met the deep-rooted traditions of the Lakota, their love blossomed. In the evenings at Fort Yates, under a canopy of stars, William and Winyan-Waste would walk along the riverbank, sharing stories of their respective worlds, their hearts beating in quiet unison despite the chasm of culture and duty that separated them, quietly defying the era’s prevailing norms and setting the stage for a profound union that straddled two worlds.

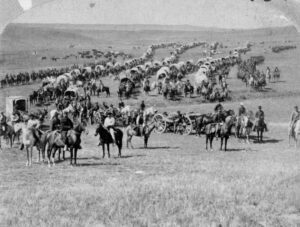

Their time together was cut short. William was summoned back to duty with a heavy heart as he parted from Winyan-Waste, vowing to return. In June 1874, he and his comrades from Company G joined the Black Hills Expedition under George Armstrong Custer’s command. The Black Hills were sacred to the Lakota Sioux, off-limits to white settlers by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, yet the promise of gold would soon challenge such agreements. That summer, the mission, ostensibly to survey the region’s natural resources, was fundamentally a quest for gold. They mapped the area, scouted sites for a military fort, and assessed the potential for a railroad, foreshadowing the inevitable treaty violation.

The expedition was vast, comprising over a thousand men including cavalry, engineers, and scientists. It became a spectacle, capturing the nation’s imagination with visions of a gold-rich West ripe for conquest and settlement. When Custer publicly confirmed the presence of gold, it ignited the Black Hills Gold Rush. Settlers and miners, like a torrent, surged into the region, founding towns such as Deadwood and directly challenging the treaty’s terms. This violation deepened hostilities with the Dakota Sioux, setting the stage for the devastating Great Sioux Wars, which would soon include the infamous Battle of Little Big Horn—a conflict which would reverberate strongly throughout Company G.

In September of 1874, after a grueling 1,125 miles, Company G returned. William, his duty temporarily fulfilled, hastened back to Winyan-Waste. Their reunion, steeped in the shadows of national ambition and conflict, was a fleeting respite amidst the burgeoning storm of conquest and change. The joy of their reunion was tinged with an unspoken dread, the specter of future conflict casting long shadows over their fleeting moments of peace. The specter of future battles loomed large, hinting at the trials and tribulations still to come for William and his comrades.

About the Blog

This website was established to assist in the research the Sawn family name as well as the many surnames associated with it. It was set up to assist in the research of these families and contains related documents and photos collected over the year. The blog represents the stories and histories uncovered about our ancestors during this research.

Recent Comments

- Sabine J on The Sauer Family and Murphy’s Law

- Daniel Sawn on The Name’s the Same

- Cleo Sawn on Where are all the Sawns?

- Cleo Sawn on Who is in my family tree?

Categories

- Cultural and Regional Studies (3)

- Economic and Business History (1)

- Genealogy and Ancestry (8)

- Heritage and Legacy (1)

- Historical Context and Events (3)

- Historical Figures and Impact (2)

- Historical Records and Research (2)

- Military and War History (4)

- Monuments and Memorials (1)

- Personal Histories and Narratives (7)

- Research Techniques and Analysis (1)

- Tragedies and Accidents (3)