Soldier, Settler, Storyteller – Part 2

The following year of 1875 brought a decree that put Zahn at a crossroads: soldiers were to either marry their Indian companions or part ways. Zahn, unable to afford the dowry but unwilling to abandon his love, chose to leave the Army. This decision spared him from participating in the Battle of the Little Big Horn, a conflict that would forever change the course of American history.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, became a symbol of resistance against U.S. government policies aimed at confining Native Americans to reservations. For the U.S. Army, led by Colonel George Custer, it was a devastating defeat that underscored the complexities and challenges of westward expansion. Custer and over 260 of his men fell on that fateful day in various engagements in June 1876, facing a united force of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. Among those on the opposing side were famed leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, whose names would be etched into the annals of history for their roles in the battle.

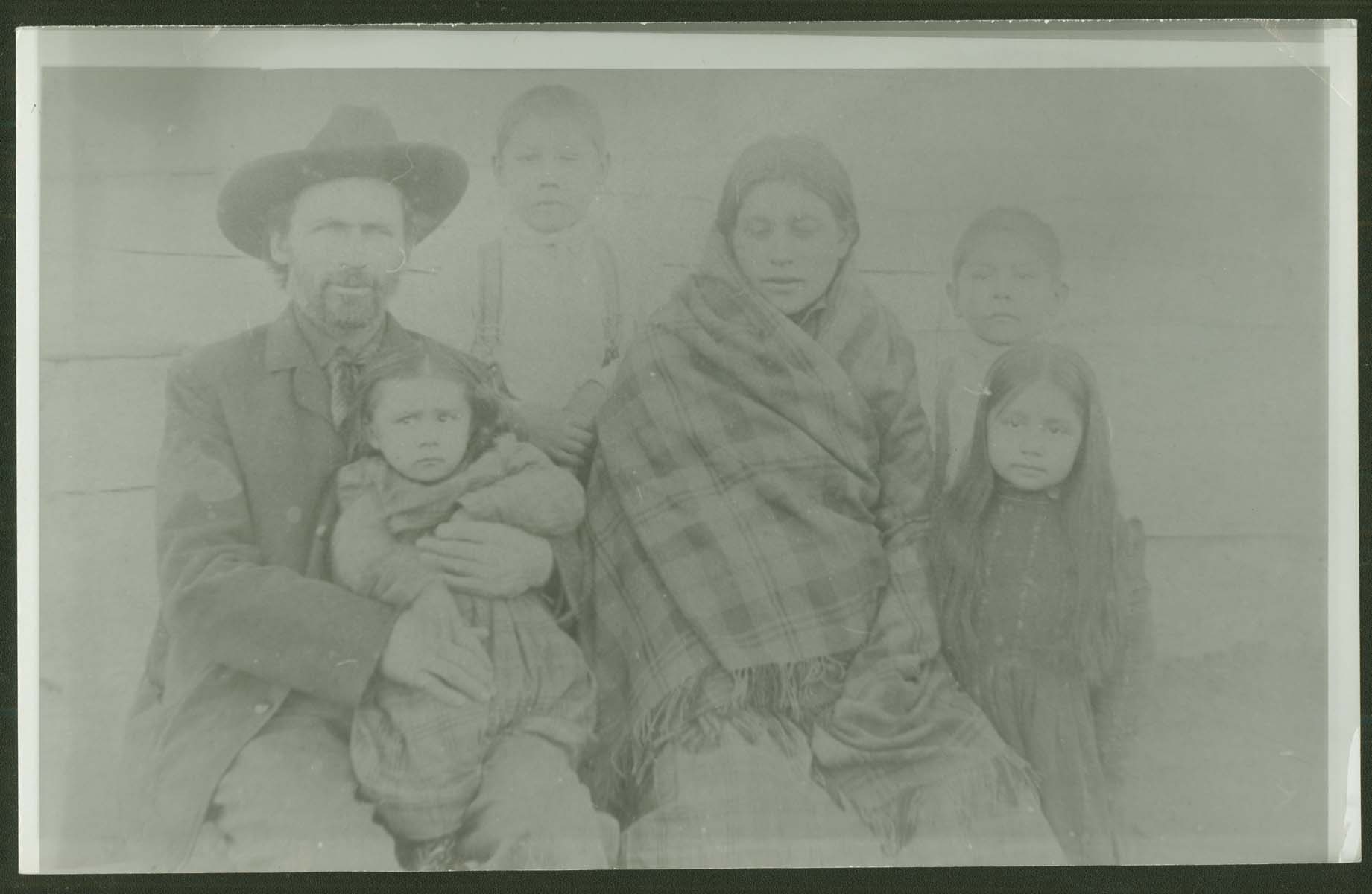

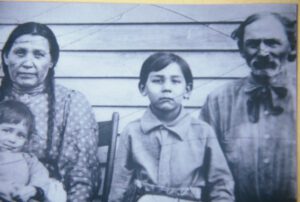

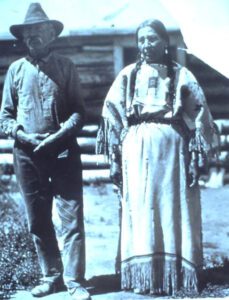

Following his departure from the military, Zahn’s life took a new direction. He became deeply integrated into the Lakota community, marrying Winyan-Waste and later, after her death, marrying Princess Kezewin (Josephine Mary), a daughter of the Hunkpapa leader Chief Flying Cloud and a relative of Sitting Bull, with whom he had an additional twelve children. Zahn’s cabin at the mouth of the Cannonball River became a hub of interaction between Native Americans and settlers, with Zahn himself serving as an interpreter and advocate for the Lakota people.

Zahn’s unique position allowed him to forge a close relationship with Sitting Bull, serving as the chief’s interpreter and witnessing the turbulent years that followed the battle, including the tragic end of Sitting Bull during the Ghost Dance movement. In the fall of 1889, the military became alarmed upon learning that Sitting Bull was conducting Ghost Dances off of the Standing Rock Reservation. They wanted him to return to the reservation so that his actions could be more closely monitored, and in 1890 William “Buffalo Bill” Cody was sent to try and persuade Sitting Bull to return to Standing Rock. Before confronting Sitting Bull, Cody stopped by Zahn’s cabin to ask him to go with him, but Zahn declined, stating that if they left Sitting Bull alone, he would return on his own accord.

Unfortunately, the U.S. government interpreted the Ghost Dance as a potential prelude to armed rebellion. This fear and escalating tensions quickly boiled over on December 15, 1890, when Indian police were sent to arrest Sitting Bull. The confrontation ended with Sitting Bull shot and killed, along with several of his supporters and Indian police. Sitting Bull’s death marked a significant moment in the history of Native American resistance to U.S. government policies and set the stage for the tragic Wounded Knee Massacre just two weeks later.

Shortly thereafter, Cody convinced Zahn to join his Wild West Show both as interpreter and storyteller, thrilling audiences with tales of the untamed West. Zahn also remained active with the Lakota people until his death on September 8, 1936.

William Zahn’s story, deeply intertwined with the Lakota people, stands as a testament to the complexities of cultural integration, showcasing the enduring human capacity for adaptation and empathy amidst the tensions of the time. His unique role in the tumultuous history of the Dakota Territory, especially set against the backdrop of the Battle of the Little Big Horn and the broader Indian Wars, highlights a moment in history where the fate of nations and peoples hung in the balance. Through his life, William emerged as a figure of unity, encapsulating how individual lives are intricately caught in the sweep of history and the relentless march towards understanding and integration.

About the Blog

This website was established to assist in the research the Sawn family name as well as the many surnames associated with it. It was set up to assist in the research of these families and contains related documents and photos collected over the year. The blog represents the stories and histories uncovered about our ancestors during this research.

Recent Comments

- Sabine J on The Sauer Family and Murphy’s Law

- Daniel Sawn on The Name’s the Same

- Cleo Sawn on Where are all the Sawns?

- Cleo Sawn on Who is in my family tree?

Categories

- Cultural and Regional Studies (3)

- Economic and Business History (1)

- Genealogy and Ancestry (8)

- Heritage and Legacy (1)

- Historical Context and Events (3)

- Historical Figures and Impact (2)

- Historical Records and Research (2)

- Military and War History (4)

- Monuments and Memorials (1)

- Personal Histories and Narratives (7)

- Research Techniques and Analysis (1)

- Tragedies and Accidents (3)