Blog Posts

Who is in my family tree?

The majority of the data on this website is the result of my research into my direct ancestors. When my sister convinced me to research our ancestry some years ago, we didn’t know much past our grandparents. I’ve kept at it, and in addition to our direct line have included information on many related families, practicing a form of “collateral” genealogy. While the bulk of my time is spent researching my direct ancestors, I’ve collected information on their siblings and their extended families, including half-siblings, step-siblings, adopted children, step-children, parents in law, etc. I’ve also included some research on families I think I may be connected to, or a famïly that just drew my interest. All are included on this “family” tree. I do this for several reasons;– Helping others with their research. I have the records and will always share what I have with others even if we may not ultimately be related. As an example, I’ve trudged through many a cemetery looking for relatives and I usually wind up taking a picture of every tombstone in the cemetery. It saves me the trouble of going back to that cemetery if I discover another relative was buried there and as a find a grave contributor I will respond to requests for photos to help others who may not be able to do so on their own. – I may find that connection sooner or later. I have been transcribing information from the records available for a very small village in Italy named Sant’Angelo d’Alife from which my wife’s grandparents emigrated. I have so far traced her direct lines in that village back to the late 1700’s. I am transcribing information from various Ferrazzano families in that particular village. Do I think their will be a connection between them and my wife, who has two 4x grandparents of the same name born in the late 1700’s ? Not a doubt. – Finding cousins. Many times I have been contacted by someone who may be no relation, but has knowledge of a family branch I was completely unaware existed. Better yet, they may have specific information on births, death, children, etc. or even photos. One never knows where those handed down bibles, family photos, and heirlooms ended up. And in the end, unless I believe that only my direct ancestry is important, is there really such a thing as “my family tree”. So, if you’re related, think you’re related based on information on this site, or have any information for people on this site, would appreciate hearing from you.

Where are all the Sawns?

For a name with only four letters, Sawn is probably one of the most mispronounced surnames around. Since the mind reads what it wants, the name usually comes out as “Swan” or “Sean”. Not only that, there’s just not many of us around. According to the 2000 census data, there were only 142 occurrences of the surname Sawn ranking it as the 114,116th most popular surname in the US. Sawn family members show up in only about 20 states with the biggest concentrations in New York, New Jersey, and Florida. Yet the family has been around the US for a while. The earliest record I have found to date is the subscription for the purchase of a book in 1794 by Daniel Sawn. He was listed in the book “Some account of the city of Philadelphia, the capital of Pennsylvania, and seat of the Federal Congress; of its civil and religious institutions, population, trade, and government; interspersed with occasional observations” by Benjamin Davies as on of the subscribers for “The Plan of Philadelphia”. He also appeared as a subscriber to a book by William Guthrie titled “New System of Modern Geography”, published in 1795. Next, Daniel shows up in the 1800 census in Roxborough Township in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Henry and Susannah Sawn, who most likely were living with Daniel during the time of the 1800 census first appear in Camden, New Jersey in 1809 as members of the first class of the Third Street Methodist Episcopal Church. It is from these two gentleman that the majority of Sawn’s currently living in the US descend. There is one other Sawn family. These are descendants of an individual from Germany named Frederick Zahn (b 1875), whose son William (b 1845) legally changed his name to Sawn in 1871 while a resident of Michigan. So chances are, if you’re a Sawn living in the US, you’re related to someone in this tree.

The Sauer Family of Camden

This photo is a family photo of my GG Grandfather John William (Wilhelm) Sauer taken about 1910. John came to America in 1868 at the age of 18 with his two brothers, Louis (Ludwig) and Philip (Johann Philipp). Their parents sent them to America to avoid military service at home in Germany. In addition to their parents, Wilhelm and Elisabetha (nee Creter), they left behind two sisters, Anna and Agathe. To my knowledge, only Louis ever made it back to Germany to visit. After landing in New York, Louis ultimately stayed in that city. John and Philip continued south. John made his way down to Richmond, Virginia and there met and married Caroline Hetzer, a daughter of German immigrants. I don’t know whether Philip made the trip to Virginia, but he ultimately ended up in Philadelphia in the late 1800’s. John also moved back to Philadelphia and stayed for a time working as a factory manager but eventually moved the family to Camden, New Jersey, where they remained. I have yet to find any trace of Philip beyond a reference to him being a waiter in Philadelphia in 1883. But unless he had any descendants, the Sauer surname from this particular branch, like many surnames, was only around for a brief period. With the passing of Richard Henry Sauer in October, 2010 there are no more male descendants from this line. To see who’s who in the photo, please navigate to the “Genealogy Photos” under the “Media” tab and search for Sauer. There is also a photo taken at the same time of the Sauer’s with their respective spouses.

The Sauer Family and Murphy’s Law

So, no sooner do I complete my recent post with the fact that I could not find any information regarding the whereabouts of John Sauer’s brother Johann Philipp than Murphy’s law kicks in. Not too long ago I was just doing some random searches on FamilySearch when I came across a Philadelphia death certificate for a John Phillip Sauer. He died on January 8, 1894 from Tuberculosis. How am I assuming this is my GG grandfather’s brother. First, there are very few, if any, John or John Phillip Sauer’s living in Philadelphia at the end of the 19th century. Secondly, he is noted as born in Germany about 1858 on his death certificate. This would make him younger than his older brothers by 6 and 10 years. This correlates to the family stories that have been passed down. But most importantly, is the testament of John William’s stepmother Henriette Sauer, that was drawn up August 6, 1883. In it, she lists the names, locations, and occupations of her 5 stepchildren. It is noted that Johann Philipp is a waiter living in Philadelphia at the time. The occupation on the death certificate….waiter. Further research indicates that Johann Philipp was married at the time of his death and further research of census information, etc. shows that Dora Holder in 1888 and had 2 children. They were John Philipp (born 1891) and Annie (born 1893). John died in Atlantic City in 1979 at 88 years of age. He married Sarah Heller in 1928. Presumably, they had children…so the Sauer line may yet be thriving in the United States.

The Results Are In…

So I received my FamilyTreeDNA results and the first thing I wanted to check out was my ethnicity. I grew up with the assumption that my Dad’s family was from Germany and my Mom’s family was from Ireland. While my research to date has shown me that’s not entirely accurate, I figured it wasn’t far off the mark. A look at the results showed I was >99% European, so no surprise there. A look at the breakdown of my European ancestry shows 47% British Isles, which basically covers all of the United Kingdom and Ireland. The percentage was higher than I expected. I’ve been doing research on my Dad’s side which suggests there is some English ancestry dating pretty far back through Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, but didn’t think there was enough to impact the results. The second largest group, at 36%, was Southeast Europe. This covers present day Italy, Greece and several of the Western Balkan states including Bulgaria, Croatia, and Slovenia. The next group at 16%, was Scandinavia which includes present day Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Admittedly, both of these groups perplex me. My dad has a large number of German ancestors and my mom a few. I have traced these lines back to the 1700’s and in some cases, the 1600’s. I would have thought there would be a presence in the West and Central or East Europe clusters (both of which include present day Germany). With respect to my Y-DNA, there were no matches to anyone that would suggest statistically significant match closer in than 4 generations. Similarly, the mtDNA did not show any potential matches of note. On the other hand, the family finder test shows there are 37 individuals out there who are 4th cousins or closer. I don’t recognize any of the names, but a little more than half have supplied their family tree. So it looks like a closer review of the submitted family trees would be in order.

The Promise of DNA

As the paper documents for researching my family are starting to peter out, I’ve become interested in taking a look at DNA as a means of filling in some of the blanks and to reinforce some that might be a little too circumstantial. So I sent my sample off to Family Tree DNA. I chose them because in addition an autosomal DNA similar to those offered by AncestryDNA and 23 and me, they will test your Y-DNA and mtDNA. DNA testing is for your genetic relationships. In other words, you have a genealogical tree that contains all your cousins, ancestors, etc. based on your paper research. And you have a genetic tree that contains only those ancestors that contributed to you DNA. While there is overlap, not everyone in your genealogical tree contributed to your DNA since bits and pieces are lost each generation. After about 5 generations, your genealogy tree will be much larger than you genetic tree. In short, the atDNA is that which you get from both parents. Roughly, you get 50% each from your mother and father. And it roughly halves with each generation back. So you get 12.5% from each of you four grandparents and 6.25% from each of your eight g-grandparents. This test is good for finding genetic (vs genealogical) cousins. It’s likely you’ll share DNA with your genealogical cousins up to about the 4th cousin relationship, but the likelihood declines rapidly after that. So this test is great to find cousins who have a fairly close genetic distance. In addition, atDNA will give you a fairly accurate prediction (more on that in a future post) of your ethnic makeup. Y-DNA is the unique DNA passed from father to son. An exact copy is passed down over the generations, but deviations do occur at a fairly characterized rate. So this test can help find paternal cousins and because the deviations are consistent, it will give a reasonable estimate of how far back our most common ancestor is. MtDNA, on the other hand is uniquely passed down through the maternal line in that only a mother can pass it down. While I may inherit, my mother’s mtDNA, I did not pass it down to my daughters. My sister, though, will have passed our mother’s mtDNA on to her daughters. mtDNA is not useful to “fish” for cousins because it mutates very slowly. So a genetic match may be a close cousin or several generations away. I don’t have a lot of info on my maternal line, so I’m hoping this test may help me narrow my search. More to come on my DNA experience in future posts, but I am convinced that DNA testing is as important a tool in genealogical research for proving relationships as any paper document. So much so that I have been recruiting family members to test as well. So if we’re related and you’re willing to participate, please get in touch.

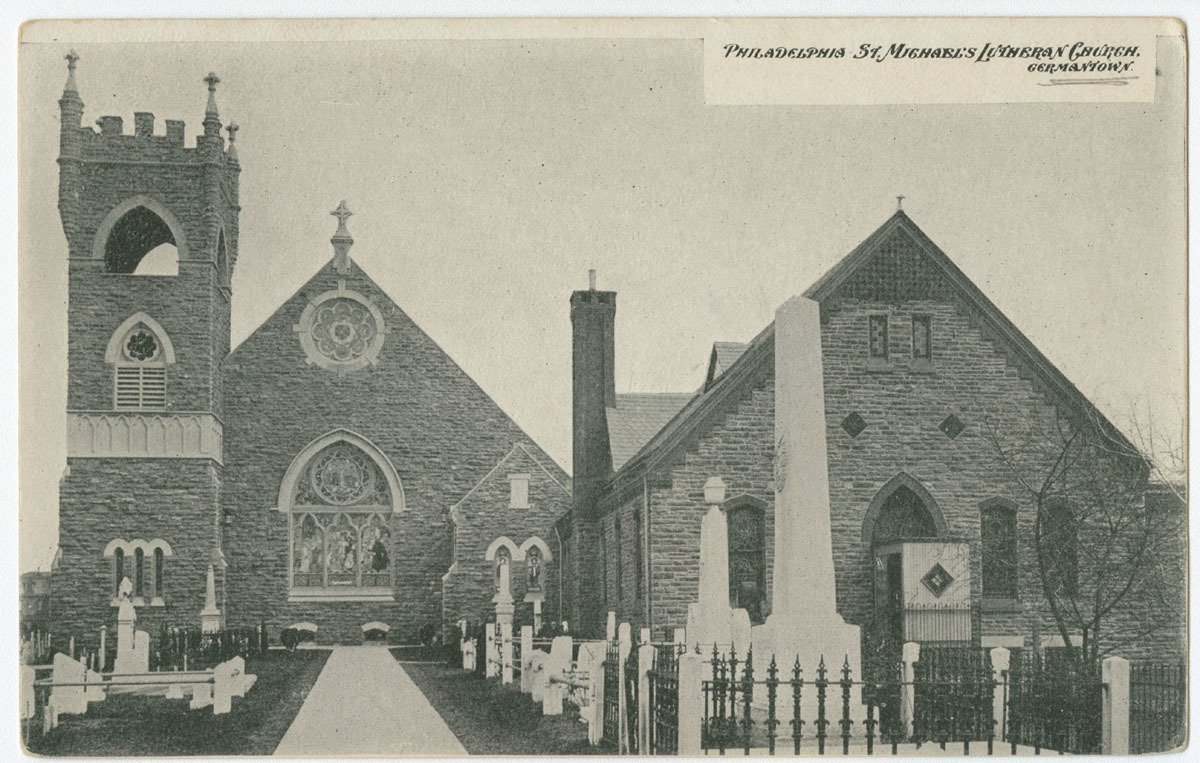

The Name’s the Same

Like many of us, I imagine, I never knew the origin of my family name. I find family names to be of the upmost importance when seeking the history of our ancestors; some versions of a name may carry information that may have otherwise been hidden to us. When it comes to Sawn, there have been many variants suggested, and family lore from different branches has hinted over the years at Van Sawn, or alternatively, Van Saun. In my more recent research, I came across a baptismal record for St. Michael’s Church in the Germantown area of Philadelphia. This church has birth dates that match up to my 4th great-grandfather, Henry Sawn, and another Sawn named Daniel. I knew both men had lived in Germantown and have based an assumption that were related to one another on this. Records for St. Michael’s Lutheran Church note the baptism of four young children under the surname Zahn, on August 23, 1779. Heinrich, Daniel, Johannes, and Elizabeth were all under ten years of age at the time of their baptism. They had unfortunately lost their father, Christian Zahn, in April of that year. He originally immigrated from Prussia, and died aged 46. Their mother, Susanna Zahn, remarried in January 1, 1784. She was wed to a man named Johann Lutz, in St. Michael’s Church. Elizabeth Zahn, who was born just 25 days before her father died, would tragically die just three months after him, in November 1779. Heinrich, Daniel and Johannes were apprenticed in various trades, which they would continue to practice for the remainder of their lives. Heinrich Zahn, or Henry as he went by in later years, apprenticed in Philadelphia with a carpenter named Andrew Greble, who was a veteran of the Revolution. Interestingly Andrew’s great grandson, John Greble, was a West Point graduate and the first regular Army Officer killed in the American Civil War. Henry eventually settled in Camden, New Jersey as a successful cooper. He passed this trade down to his own three sons. Daniel Zahn remained in the Germantown section of Philadelphia. It is thought that he apprenticed in the paper-making business with Jacob Rittenhouse, whose grandfather, William Rittenhouse, opened the first paper-making mill in America. We do know that Daniel worked at the mill for Jacob from 1798-1803, before moving to Belleville, New Jersey. Daniel ultimately settled in Springfield, Massachusetts, exercising his trade as a paper-maker. Johannes, later adopting the name John, apprenticed on a farm in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. He married and moved to practice agriculture in Loudon County, Virginia. It was here that his children were born and raised. So, what is it that binds the descendants of these three men? The answer is written in their DNA. While Johannes continued to go by the last name Zahn, Heinrich and Daniel started going by the last name Sawn at some point during the 1790’s. Matches on a recent DNA test I took with AncestryDNA show positive matches between myself and the descendants of four of Johannes’s children. Though there may yet be more undiscovered matches to Johannes’s family, I am now convinced that their father, Christian Zahn, is indeed my fifth great-grandfather. I have learned though this experience that, unfortunately, paper trails can at times become stretched or circumstantial. If this happens, it is important to take advantage of ever-developing technology. When required, DNA evidence can step in, to ultimately provide a solid link that ties relatives together.

The Daltons Come to America

Ireland is a beautiful island located in northwest Europe. Separated from Great Britain by the Irish Sea, the North Channel, and St. George’s Channel, it’s the 2nd largest island of the British Isles and the 20th largest island on Earth. Geopolitically, Ireland is divided between the Republic of Ireland, which covers 83% of the island and contains 73% of its inhabitants, and Northern Ireland, which remains part of the United Kingdom. The divide has been in place since 1921. Figure 1: A current map of Ireland showing the border between Northern Ireland (White) and the Republic of Ireland (Cream) Ireland experienced an economic boom in the late 20th century, in industries such as financial services, pharmaceutical and medical technology, software and IT services, and the export and trade industry. This boost to the economy gave the island’s inhabitants a standard of living that can now be compared against other first-world countries across the world in terms of average quality of life… But it wasn’t always this way. During the mid-19th century, agriculture was the main economy of Ireland. While this was not uncommon, agricultural management in Ireland saw widespread problems by 1845. Farms had grown unsustainably small due to mass subdivision and were poorly managed by largely absent landlords. This resulted in a vast majority of the population relying on the humble potato for subsistence; as a low maintenance and high-yield vegetable that was cheap to sow, it was virtually the only crop that could be grown in sufficient quantities to feed a poor family. While there were multiple varieties of potato available in Ireland, the Irish were heavily dependent upon only two common, high-yielding types. This was a disastrous contributor to the tragedy that soon struck the island. In 1845 Ireland saw the accidental introduction of Phytophthora Infestans, a strain of water mold capable of quickly decimating large plots of sown land. While it is unknown exactly where it came from, we do think North America was the likely culprit; Ireland’s trade partner had experienced crop failure due to the same mold for two years prior. Thanks to unusually cool and moist weather patterns across Ireland that year, pockets of mold soon thrived into huge colonies, and most of the crops available to the population were destroyed by a disease known as Late Blight. From 1846 through to 1849, potato crops continued to be destroyed by the disease. In Ireland’s history, this is known as the Irish Potato Famine. Figure 2: The Philadelphia Irish Famine Memorial. Dedicated on 10/25/2002, the memorial is located on Front St. near Penn’s Landing and was sculpted in bronze by artist Glenna Goodacre (1939-2020). During this period, Ireland’s population dropped at an alarming rate; from a healthy 8.4 million before the Famine to 6.6 million by 1851. While exact figures may never be known, it is thought that 1 million people died from starvation or other famine related diseases. The remaining 2 million people fled the country to England, Scotland, North America and Australia. Escaping the disease and starvation in their homeland was a challenge, to say the least. Crowded and disease ridden, with little to no food or water, the vessels that carried Irish refugees across the Atlantic were soon referred to as ‘coffin ships’. While it was the cheapest way to cross the ocean and therefore the only means of escape for many desperate families, mortality rates as high as 30% were not uncommon. The risk was no greater than staying in their devastated country, but to uproot entire generations to board these vessels, knowing many would never set foot on shore again… It’s hard for us to imagine, but it happened, and we all know continues to happen today. Figure 3: Surviving Irish refugees entering Ontario, Canada, after fleeing the Famine. It was during this difficult time that the Dalton branch of my family came to the United States. Departing from County Cork, a region in Ireland known for its coal mining, they ended up in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania; a coal mining region in the Appalachian Mountains. It is unclear exactly what year they immigrated from Ireland or if the family came together or separately, but by 1850 my Dalton family was living in the town of Blythe. As seen in the 1850 census, the entire family unit included: Family Member Age Mary Dalton 60 Thomas Dalton 29 Patrick Dalton 28 John Dalton (Elder) 20 George Dalton 17 John Dalton (Younger) 7 <—My gg-grandfather According to records found to date, Mary is the mother of the four eldest boys. We also know that Mary’s husband was named George. He was most likely deceased by 1850, but it’s unclear whether he died in Ireland, during the ocean voyage, or after arriving in America. I was glad to find the death certificate of John (Younger), my 2nd great grandfather. While it was obviously unlikely that he was Mary’s son due to his age, I was surprised to see that his death certificate lists his parents as Francis and Ann Dalton. This leaves his relation to the family a bit of a mystery. Unfortunately, there are no more known records of George, Francis or Ann Dalton. I assume all three of them passed away prior to 1850. Again, the whereabouts of their deaths and burials are a mystery. Recent tests through AncestryDNA have revealed positive DNA link from my ancestor John (Younger) Dalton to Mary and her sons. Based on the generational gaps within the DNA matches, it appears that John is Mary’s grandson, and that Thomas, Patrick, John (Elder) and George are his uncles. It was wonderful to finally place a title on their relation. I am in the process of expanding the family tree to include all of the descendants of Mary and George Dalton. I hope of learning more about the history of this branch to my larger family, their passage to America, and their struggles to forge a path to the ever-elusive American Dream so many chased at the time. If you are a descendent of the Dalton family, or a related family, please contact us. We would certainly welcome any new information and the opportunity to meet a new relative!

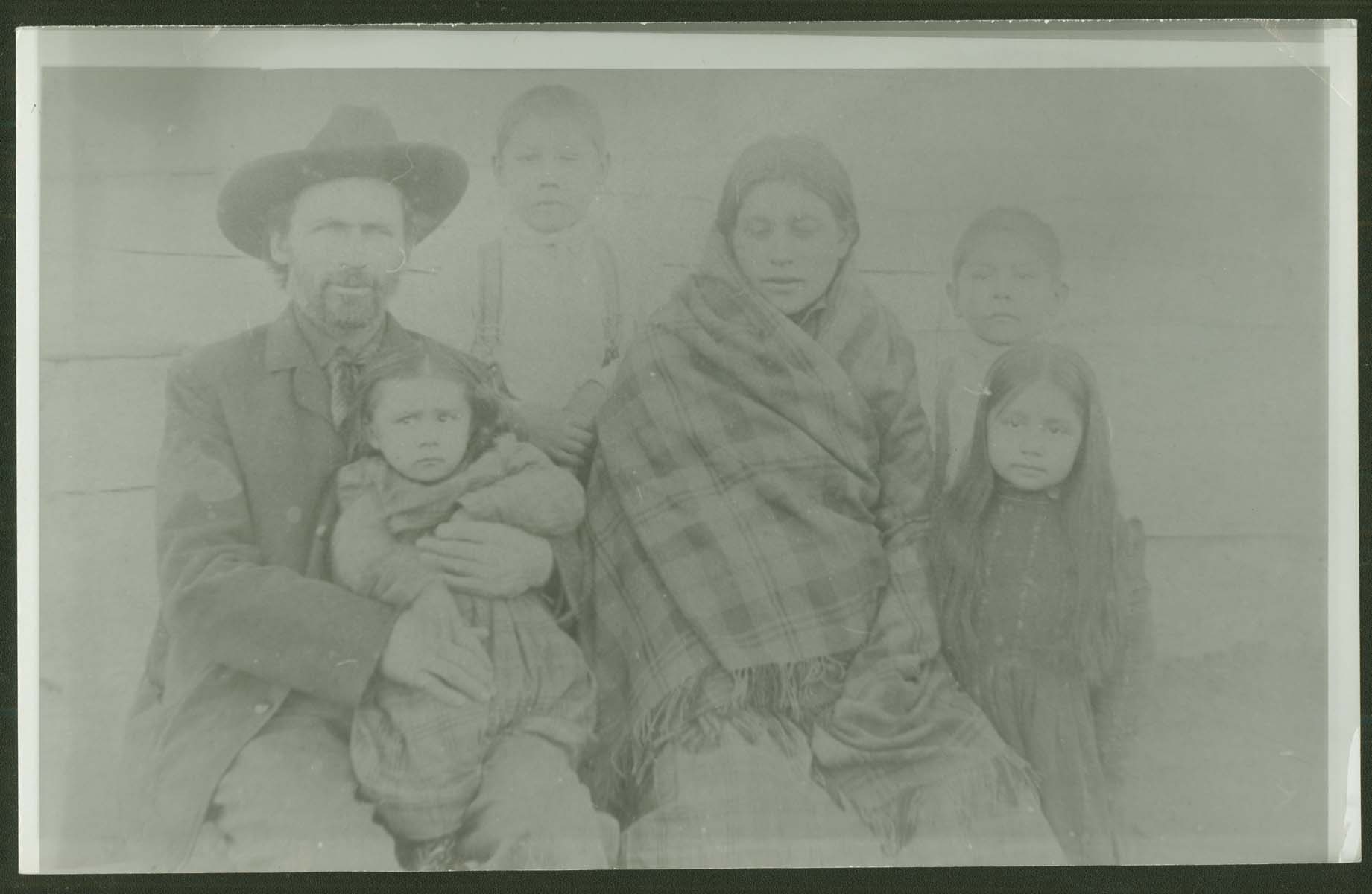

Soldier, Settler, Storyteller – Part 2

The following year of 1875 brought a decree that put Zahn at a crossroads: soldiers were to either marry their Indian companions or part ways. Zahn, unable to afford the dowry but unwilling to abandon his love, chose to leave the Army. This decision spared him from participating in the Battle of the Little Big Horn, a conflict that would forever change the course of American history. The Battle of the Little Big Horn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, became a symbol of resistance against U.S. government policies aimed at confining Native Americans to reservations. For the U.S. Army, led by Colonel George Custer, it was a devastating defeat that underscored the complexities and challenges of westward expansion. Custer and over 260 of his men fell on that fateful day in various engagements in June 1876, facing a united force of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. Among those on the opposing side were famed leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, whose names would be etched into the annals of history for their roles in the battle. Following his departure from the military, Zahn’s life took a new direction. He became deeply integrated into the Lakota community, marrying Winyan-Waste and later, after her death, marrying Princess Kezewin (Josephine Mary), a daughter of the Hunkpapa leader Chief Flying Cloud and a relative of Sitting Bull, with whom he had an additional twelve children. Zahn’s cabin at the mouth of the Cannonball River became a hub of interaction between Native Americans and settlers, with Zahn himself serving as an interpreter and advocate for the Lakota people. Zahn’s unique position allowed him to forge a close relationship with Sitting Bull, serving as the chief’s interpreter and witnessing the turbulent years that followed the battle, including the tragic end of Sitting Bull during the Ghost Dance movement. In the fall of 1889, the military became alarmed upon learning that Sitting Bull was conducting Ghost Dances off of the Standing Rock Reservation. They wanted him to return to the reservation so that his actions could be more closely monitored, and in 1890 William “Buffalo Bill” Cody was sent to try and persuade Sitting Bull to return to Standing Rock. Before confronting Sitting Bull, Cody stopped by Zahn’s cabin to ask him to go with him, but Zahn declined, stating that if they left Sitting Bull alone, he would return on his own accord. Unfortunately, the U.S. government interpreted the Ghost Dance as a potential prelude to armed rebellion. This fear and escalating tensions quickly boiled over on December 15, 1890, when Indian police were sent to arrest Sitting Bull. The confrontation ended with Sitting Bull shot and killed, along with several of his supporters and Indian police. Sitting Bull’s death marked a significant moment in the history of Native American resistance to U.S. government policies and set the stage for the tragic Wounded Knee Massacre just two weeks later. Shortly thereafter, Cody convinced Zahn to join his Wild West Show both as interpreter and storyteller, thrilling audiences with tales of the untamed West. Zahn also remained active with the Lakota people until his death on September 8, 1936. William Zahn’s story, deeply intertwined with the Lakota people, stands as a testament to the complexities of cultural integration, showcasing the enduring human capacity for adaptation and empathy amidst the tensions of the time. His unique role in the tumultuous history of the Dakota Territory, especially set against the backdrop of the Battle of the Little Big Horn and the broader Indian Wars, highlights a moment in history where the fate of nations and peoples hung in the balance. Through his life, William emerged as a figure of unity, encapsulating how individual lives are intricately caught in the sweep of history and the relentless march towards understanding and integration.